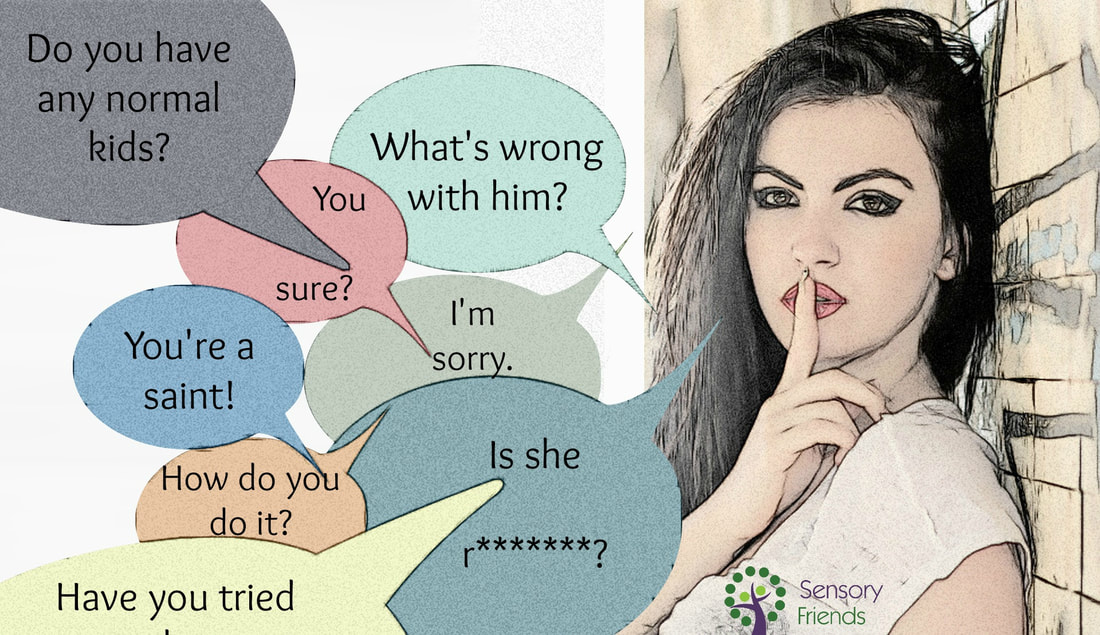

I wrote this article based on my own experiences in the community with my son who has autism. I have heard each and every one of these statements and, sadly, I still do today.

What’s often asked:

1. “What’s wrong with him?”

What I’m thinking:

Take a deep breath and remember your lines.

What I might reply:

“My child has Autism. He is making incredible learning gains, and we’re really proud of him.”

What’s the truth?

Parents of children with disabilities prefer that you ask questions about their child over staring at them, or passing judgment on their behavior or differences. However, asking “What’s wrong with him” gives the impression that you only took notice of something in a negative way. You didn't bother to notice her smile, his playful manner, the sneakers he was sporting, how fast she ran, nothing – just the distinct difference from that child and others. This frightens parents because it makes them wonder if the world will ever embrace their children without prejudice and disgust.

Try this instead:

If you’re at a playground or public place you may ask, “How does your son prefer to communicate? What does she like to play with?” Or, if you’re in a supermarket and witness an outburst, you could ask, “Is there anything I can do to help?” Please keep in mind that you may not always receive a positive response from parents dealing with an outburst or meltdown. The truth is, they’re not accustomed to being offered help. If they’re dealing with a crisis at that moment, they may not be the friendliest people. Please be patient with them, they’re dealing with more than you can ever imagine.

What’s often said:

2. “I’m so sorry”.

What I’m thinking:

Here we go again.

What I might reply:

“Please don’t be, he’s great.”

What’s the truth?

I know it’s natural for us to feel we have to comment on something that sounds unusual to us. Please understand that there’s no worse feeling than being made to feel pitied. Being “sorry” implies that the family leads an unfulfilled life of suffering. Their child is a blessing just as any child is.

Try this instead:

What kind of supports are there for you and your family? Is there any help or services available in the community?

This tells parents you really care and that you’re genuinely interested in learning about their child and their life.

What’s often said:

3. “I don’t know how you do it. I wouldn't have made it”.

What I’m thinking:

Yes, I get to decide what color cape to wear every day, while you should just be stoned. What does that comment even mean? If your child had a disability you would abandon them?

What I might reply:

“The truth is I know you’re a wonderful parent and you would do everything you could for your child just as I do.”

What’s the truth?

Parents hear things like, "We are only given what we can handle” all the time, and it isn't always taken as a compliment. We all do what we have to do for our children because it’s driven by love. If you were given the same path, you would do the best you could with what you had, just like I do.

Try this instead:

“I don’t know much about what your day is like, but I admire the way you handle things.”

What’s often asked:

4. Is she talking yet?

What I’m thinking:

This is an opportunity to explain Richie's disability.

What I might reply:

“No, but we are hopeful that speech will come. At this point, we still use pictures, sign language, and/or augmentative devices for communication.”

What’s the truth?

Please resist asking parents if their child is talking, walking, writing, running, or anything yet. It’s painful enough for us to notice just how behind or different our child is from other children their age. When we’re asked this type of question, it makes us feel like there’s some sort of “cut-off or dead line” we have to meet and we’re running out of time.

Try this instead:

This is a very delicate topic. Control your curiosity and ask nothing. Allow parents to lead the topic when it comes to their child’s abilities. The truth is many children with varying disabilities make learning gains at different times and in different ways. These types of questions are intrusive and should only be asked by caregivers, specialists or doctors. They truly have no place in ordinary conversation. Think about it, how often do you ask a friend what their child’s report card grades were? Did you ever ask a friend or colleague if their dreams in life came true yet? I dare you to try it: “Hey, what are you forty? Did your ever acquire your dream job you told me about when we were kids?"

What’s often asked:

5. Are you sure? He doesn’t look like he has a disability. I think he’s going to be just fine.

What I’m thinking:

Wow. You’re clairvoyant and you have a medical degree. You’re right, I just made it up.

What I might reply:

I know he may appear not to have a disability, but he has ******. This disability doesn't change a person’s appearance.

What’s the truth?

There are disabilities, such as Autism, ADHD, Tourette’s syndrome, and many others that do not impact the individual’s physical appearance. Making this type of statement is a complete waste of time to a parent that has undergone countless visits to the doctor, specialists, and evaluations, only to hear that someone doesn't think it’s true.

Try this instead:

I don’t know much about *****. How can I learn more about it?

What’s often asked:

6. Thank god you have a “normal” kid, right?

What I’m thinking:

How can this question be a normal thing to ask?

What I might reply:

“I’m always so thankful that I have two terrific kids. Each of my children have their strengths and attributes. They may be very different, but I love them both and feel lucky to have them in my life.”

What’s the truth?

All parents love their children and if they have more than one, they love them all the same. It’s true there is a soft place for children with disabilities that consume most of their parent's time and attention (often taking away from their siblings and other family members), but these are the necessary sacrifices that families make for children with special needs. My daughter was twelve when her brother was born. She absolutely loved and adored him from day one, she still states he is the most important person in her life today. No parent ever wants their child to be treated as “less.” Making a comment like this one implies that a child with a disability is less than any other child, and that statement is so far from the truth.

What’s often asked:

7. “Did you smoke or drink while you were pregnant? Did you know while you were pregnant?”

What I’m thinking:

Be still Christine. Help this person understand the impact of their questions.

What I might reply:

“I had nothing to do with directly impacting my child’s probability for having a disability. Please research information about a specific disability before asking another parent such a question.”

What’s the truth?

Parents of children with disabilities have enough to deal with already without having to feel judged or worse yet, blamed for their child’s having a disability. Asking a woman if she smoke or drank while she was pregnant implies that she did something wrong and that she caused her child to be born with a disability. Asking her if she knew about the unborn’s diagnosis while she was pregnant sounds like you’re really asking if she consciously made the decision to keep the baby, even after finding out the unborn was going to live a life filled with different challenges. Either way, both questions are completely inappropriate and should never be asked. You have no idea if that person (or their child) was recently diagnosed and they are still dealing with raw emotions that are still very fresh and painful. Depending on the cause, type of disability, and individual, it may still be very difficult for them to discuss this, not to mention that once again, it is simply a very private matter.

Try this instead:

If you must know all there is to learn about what causes the disability, please just do the research yourself. You may ask, “I don’t know a lot about this disability. How do I learn more about it?” At least this way, you’re illustrating your curiosity in a caring and non-intrusive way.

What’s often asked:

8. “Have you tried what Jenny McCarthy did (or whatever some rich celebrity decided to write a book about)?”

What I’m thinking:

No, I’m afraid I haven’t tried the methods used by Jenny McCarthy, Toni Braxton, or Holly Robinson. Sadly, I don’t have the millions of dollars they do, until then, it’s trial and error with doctors, therapists and educators we collaborate with and trust!

What I might reply:

“Honestly, many methods are not always going to work on all children. Sadly, many of these methods are costly and not covered by insurance. We’ve been working with a team of specialists at school and at the doctor’s office.”

What’s the truth?

Parents shouldn't have to made to feel guilty about not being able to afford to try expensive methods that promise to “cure” or “heal” their child’s disabilities. There are literally hundreds of therapies, natural remedies, medications, treatments and programs that each have different success rates with different children. Sadly, there are just as many gimmicks that prey on parents desperately looking for any sliver of hope. Personally, I can’t afford these expensive diets, teams of specialists, or programs. Does that mean I don’t want to “cure” my child? Is my child punished because of my socioeconomic status? Parents spend hundreds, sometimes thousands of dollars on therapies, medication and other programs. Please be patient if you detect annoyance in their response.

Try this instead:

“I have heard of so many therapies, special diets and medicines that are being used. How do you know what will work for your daughter?” This does so many things for a parent. You opened the door to a controversial discussion, but you took an appropriate and neutral approach. Its very likely that the parent you’re talking to is still learning about and navigating many treatments, programs and systems. Having a child with a disability is not a process. It’s not something that just passes. As your child grows older, there will be new things to learn and try, just as there will be different challenges along the way.

What’s often said:

9. Is he r******d?

What I’m thinking:

To this day, I'm usually stifled by this question- it only lasts a few seconds, but even after all this time it's still painful to hear.

What I might reply:

“You should know that term is politically incorrect, and that members of the disability community are deeply offended by the use of this word to describe people with cognitive disabilities. But to answer your question, my child was diagnosed with ________, and has many challenges, but that word is not one of them."

It is completely up to the parents whether or not they choose to disclose their child’s disability. I personally prefer to take every opportunity available to try and educate people. I don’t want any individual or parent of a child with a disability to have to hear those words.

What’s the truth?

Just like so many other former medical terms such as, moron, imbecile, or idiot, the “r” word is frowned upon when used to describe individuals with disabilities. Many years ago, these words were initially known as medical terms for describing the mentally challenged. Unfortunately, people recklessly began to use them as words to insult one another while at the same time degrading and humiliating the individuals dealing with mental and cognitive afflictions. Have you ever heard someone say, “I’m not an invalid, you know.” I imagine this word will one day join the others just mentioned. I understand that the true definition of comedy is that it is someone else’s misery. And sometimes it may be difficult to gauge the appropriateness of when certain things should and shouldn’t be said. There are many degrees of right and wrong in our society, and these scales are measured differently by everyone. Regardless of what societal standards may or may not be, in the disability community, it is never okay to use these words to describe another in public.

Try this instead:

“What are the kinds of challenges your child faces in everyday life? I’d really like to know about her condition and what type of help you receive.”

Approach a parent this way and you may just appease your curiosity and learn about this child. Please keep in mind that most parents won’t mind sharing information with you. However, you may encounter parents that prefer to keep their lives and their children’s disability private, and just as it’s your right to speak what you wish, it is their right not to.

What’s often asked:

10. “So, she’s probably gonna end up in an institution, right?”

What I’m thinking:

Every possible thought I can to help stop me from shedding a single tear in your presence.

What I might reply:

“Honestly, I don’t know what my daughter’s future holds today. I can only hope that with continued supports and better instruction, her chance of living independently will increase as she gets older.”

What’s the truth?

This has to be one of those topics parents want to talk about least. In the disability community, we believe that children and adults with disabilities should live in nurturing, inclusive, and natural environments. However, it may be a reality for many of us to consider placement at one point or another, and there is no shame in having to make that decision either. Please understand that it is still a heartbreaking process. The reality may be that as parents, we lack the training, resources, funding, and the ability to care for a family member full time - at all times is not always possible. A group home or care outside their child's natural environment may be best. Still, it is not a pleasant thought. You may feel a parent is in denial, or avoiding the inevitable. Whatever your thoughts may be, please don’t confuse denial with hope. No one has the right to strip a parent of their hope. In this instance, it’s best to keep your thoughts to yourself, unless a parent asks you specifically for your thoughts on the matter.

Try this instead:

Please note that there is no reason that can ever justify asking a parent this question. It is insensitive, and it is an extremely delicate topic for any parent. I recommend saying nothing about it at all.

** If by chance, your friend or loved one is upset and brings up the topic, it is because they long for the reassurance they will not be judged or thought of as “giving away their child.” In this special exception, I would recommend that you be supportive, not curious. Say something along the lines of:

“I can’t begin to know or understand what you’re going through. I can only say that I care about you both. I have watched you with (child’s name) for years, and I have witnessed the care and love you share. That’s why I know that your decision (whatever it is) will be the right one because you have always handled everything so well. It’s my understanding that these things don’t have to be a permanent decision. If you feel that this decision was not the right one at this time, you can change your mind and that’s that. Whatever you decide to do, I will support you and I will be here for you.”

If you disagree with a parent who is considering residential placement for their child and you can’t bring yourself to say something supportive, then please say nothing.

I know ten is a great way to end this, but I have one last classic question I get for having a child with Autism:

What’s often asked:

“What special abilities or talents does he have? Can he play an instrument or solve mathematical equations?”

What I’m thinking:

Yesterday afternoon, after reading my mind and discovering that I really didn’t have any plans on taking him, my son teleported himself to the beach and disappeared right before my eyes.

What I might reply:

“My son has many abilities I’m proud of, and I’m sure there are many things he can do that we haven’t yet discovered. Contrary to popular belief, not all people with autism or cognitive disabilities have savant or special skills.”

What’s the truth?

When the movie “Rain Man” hit the screens in the late 80’s, my son was just a twinkle in my teen-aged eyes. I do remember it was the first time I’d heard the word, “Autism.” While the movie did bring awareness to the world, sadly, a stigma was attached to it. People are always under the impression that individuals with autism are savants, or have a unique talent. It’s true that naturally, any time you have a disability that impacts one or more of your senses, you may enhance or strengthen the abilities of your remaining senses. It does not mean that they will have super abilities, or that a position at Apple or NASA is waiting for them in the future. Not to mention that asking a parent if their child has a special talent is simply inappropriate. How would you feel if someone asked you about your special abilities? Surely, you’re not some ordinary person. Come on, don’t be shy and tell us about your super human skill.

What did you think about this article? Please let me know your thoughts and feel free to share some of the comments you've heard.

This post contains affiliate links to products. We may receive a commission if you purchase products from this site at no additional costs to you.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed